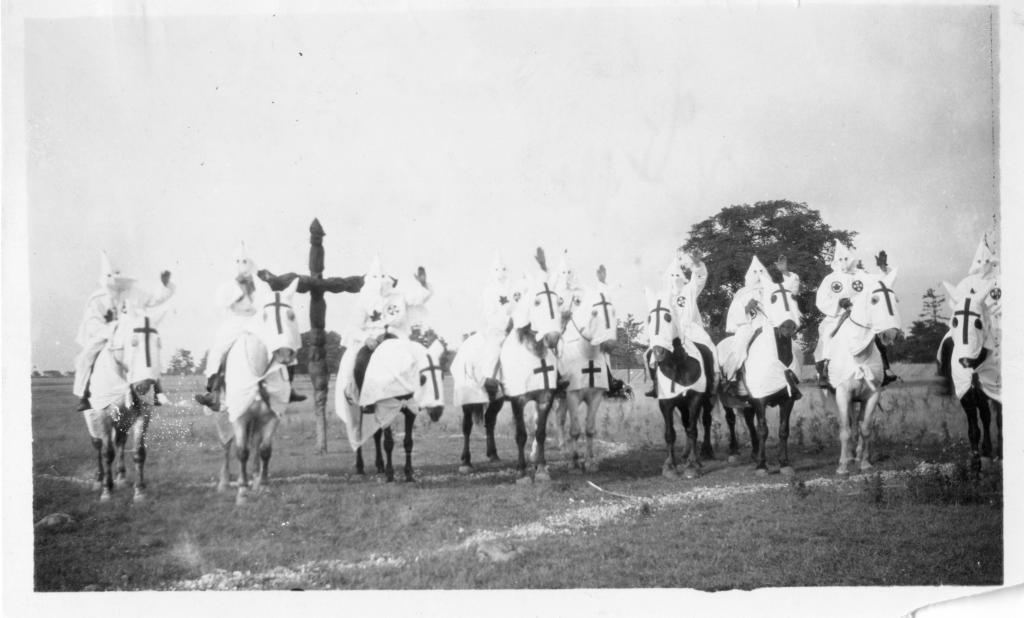

Intermixed with much of the worst of human history is a religious motivation. This can be seen in the involvement of a religious motivation in the genocide committed against American Indians and the Holocaust. More recently, this can be seen in the motivation behind tragedies such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the January 6 attack on the United States Capital. Other examples include the involvement of religion in motivating prejudice and violence directed toward members of the LGBTQ population and various cases of religious persecution.

As Blaise Pascal once reflected: “human beings never do evil so completely and so joyously as when they do it from a religious motivation.”

How can great world religions – which generally teach love, compassion, and justice – become powerful instruments of prejudice and violence?

Although acts of religiously-inspired hatred are complex and caused by many variables, one common factor concerns religious fundamentalism.

Religious fundamentalism involves a rigid kind of certainty in the possession of the “one truth” and the “one way” to live. It typically relies on a literal interpretation of a sacred text and an absolute reliance on that text. Other sources of knowing what’s true or other ways of determining what’s valuable are rejected – such as when science or a different group offers an alternative perspective – in favor of what’s unquestioningly accepted within the group.

With this all comes a strong urge for fundamentalists to form a sense of who are “insiders” and who are “outsiders.” Explicitly or implicitly, it’s easy for all of us to believe members of our groups are superior, while others are inferior. One way for religious fundamentalists to address this is to develop an evangelical zeal to bring outsiders to the inside through attempts to convert them. However, when individuals reject their arguments or invitations, fundamentalists can develop even stronger attitudes against them, to the point where outsiders can become seen as less than their human equals, sometimes even leading to consciously or unconsciously dehumanizing them. At this point, prejudice and violence toward members of the outgroup become more likely.

Because fundamentalist groups also tend to draw like-minded people to their communities, individuals in these groups often decrease or completely lose contact with those different from themselves. As a result, the kinds of reality checks most people tend to naturally have happen to them when they interact with people different from them become less likely, creating the conditions for stronger stereotypes and prejudices to develop.

Continue reading