After watching the record breaking film “Inside Out 2,” I wrote this piece for Friends Journal about how my personal journey with emotion relates to the science behind the movies and my spiritual quest. Friends Journal published it today.

Category Archives: Current Events

How to Make the Most of College

Like it has done for so many, college transformed me.

It started on freshman move-in day. My dad, my brother, and I drove 4 ½ hours from my small town of 300 people in rural Minnesota to the eye-popping, “big city” of Madison, Wisconsin. I enrolled in the University of Wisconsin because I had watched the University compete on television in Big 10 sports. Beyond that, I knew very little of what I was getting myself into. So, on move-in-day, I was astonished by the city: the grandeur of the state capital, the beauty of the lakes surrounding campus, and the expansive cultural life scattered throughout.

It took a while for me to orient myself, but I eventually settled into my new home, where I gradually encountered a variety of mind-stretching experiences. When the first semester started, I couldn’t believe I was being taught by renowned experts who raised deep issues and facilitated far-reaching discussions about ideas way beyond anything I previously realized even existed. I went with my friends to ethnic restaurants, with flavors I never tasted before. I visited an art museum for the first time. I attended massive political rallies, being exposed to people with passions and perspectives unlike any I had ever encountered.

I enrolled in what was to become my favorite college course – Environmental Science – during my second year. Most evocative for me was the weekly required lab, usually consisting of a field trip. One trip especially stands out. We met at our Professor’s home, located on the edge of a wetland outside Madison. It was a cold, January afternoon, and there was at least 6 inches of snow on the ground. The Professor eventually led us to a bubbling brook in which I was stunned to find vibrant, green watercress growing. He picked some for us to taste. Not only did I not realize any vegetable grew in this kind of winter climate, I was dumbfounded by the peppery, fresh flavor and icy, crisp texture of the watercress itself. This course, more than any other experience I’ve ever had, nurtured in me a love of nature and a commitment to conservation.

After four years of these kinds of encounters, my mind had expanded in ways that made me almost unrecognizable from the person I had been previously. In retrospect – and knowing what I know now – I believe this is because college regularly exposed me to feelings of awe.

According to Dacher Kelter, in his book, “Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life,” awe “is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that transcends your understanding of the world.” To clarify, many kinds of vastness can trigger this emotion. For instance, we might feel awe in the presence of something huge, powerful, timeless, or complex. Other people can leave us awestruck as well because of their astounding knowledge, virtue, or skill.

Twenty years of research on the emotion of awe reveals many unique positive effects. For example, awe takes the focus off of ourselves, humbling us in the presence of something beyond us. Physiologically, awe can bring tears to our eyes, chills to our bodies, and goosebumps to our skin. More broadly, awe promotes well-being and interpersonal connection. It may even decrease the body’s inflammation response.

Less research has explored how awe impacts learning and development, but a deeper inspection yields some clues. According to the great psychologist, Jean Piaget, our minds grow through two interrelated processes: assimilation and accommodation. When we assimilate, we fit new experiences into our existing mental frameworks, something not possible during awe. This is because the vastness of what we’re encountering in an awe experience cannot be comprehended with our current way of thinking. As a result, we’re absorbed into a process of trying to reduce the discrepancy between our new knowledge and our pre-existing knowledge. As we do so, we may feel confused, disoriented, or even frightened, as we feel a need to accommodate and create an expanded or entirely different mental framework. We may start to wonder and become curious about new questions. If we can successfully expand our minds in ways that incorporate the new information, we may significantly change how we think, what we believe, and potentially even how we self-identify. Even if we can’t ever fully accommodate an experience, our lives may be taken into different directions as we explore a new passion.

In his book, Keltner describes 8 common sources of “everyday wonder,” any of which could spark transformative change. These sources include exposure to lives and acts of moral beauty; the collective effervescence of big events, rallies, and ceremonies; various features of the natural world; music; visual design; great mysteries that often underlie religion and spirituality; the beginning and end of life; and ideas and truths that stretch our minds beyond what we previously believed was possible. College can regularly expose students to these kinds of stimuli.

Steven Cordes | Unsplash

Based on all this, my best advice to students is to seek awe during your time in college, inside and outside the classroom. Get involved in opportunities that stretch you, such as service learning, internships, field trips, community events, and study abroad and away programs. You may occasionally feel confused, disoriented, and even frightened because of what you’re experiencing. That’s okay: a real education requires some degree of discomfort. Pay attention to what brings you awe and follow that path, seeing what interests and passions that leads you toward. Give yourself space to wonder, to figure things out. Then, when you walk across the stage at your graduation ceremony, you, too, may find you have transformed into a version of yourself you wouldn’t have thought possible when you began.

5 Ways Religion Is Better than Spirituality

I’ve taught a course in the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality for about 20 years. As part of this course, I often invite speakers to share their religious and spiritual life stories and insights with the class. One of the most provocative perspectives ever shared came from a Jewish speaker. To paraphrase, he would say:

I know many of you consider yourselves more spiritual than religious, and I know there are many benefits to personal spirituality. However, I have a different take on this. I believe religion is better than spirituality. And I believe this is increasingly so.

The Meaning of “Religion” and “Spirituality”

Although these concepts prove extraordinarily difficult – if not impossible – to adequately define, let me clarify terms as much as possible. In general, religiousness entails behavior concerning the Sacred consistent with what an institution prescribes. Spirituality, in contrast, involves an autonomous question for what is true and meaningful regarding the Sacred, whether inside or outside an institutional context.

Thus, religiousness and spirituality are different but overlapping constructs. Religiousness involves action that harmonizes with a group’s teachings and customs to a greater extent. Spirituality focuses more on an individual’s personal and experiential quest. Common to both religiousness and spirituality is the Sacred: something that lasts forever or that evokes awe or reverence.

The Trend Toward Spirituality

Various surveys in the United States regularly ask respondents to select which of four options best describes them: (1) both religious and spiritual, (2) spiritual but not religious, (3) religious but not spiritual, and (4) neither religious nor spiritual. Results consistently show how respondents are most likely think of themselves as “both religious and spiritual.” However, individuals in these studies increasingly identify as “spiritual but not religious.” For instance, in nationally representative surveys of American adults from the Fetzer Institute, those indicating they were more spiritual than religious rose from 18.5% in 1998 to 33.6% in 2020.

Five Unique Benefits of Religion

Some might consider the notion that religion has unique psychosocial benefits – compared with personal spirituality – offensive or, maybe ironically, “sacrilegious.” However, particularly at this moment in time, in our culture, consider the following:

Continue readingOne Powerful Way to Help Young People Who Are Struggling

As a parent, an educator, and an uncle, I worry about this generation of young people.

And there’s good reason to worry.

For example, according to the recently released Youth Behavior Risk Survey, 42% of American high school students felt so sad or hopeless during a 2-week period in 2021 that they stopped doing their usual activities (in 2011, this percentage was 28%). Sadness and hopelessness were especially high in females (57%) and LGBTQ youth (69%). As demonstrated by social psychologist Jean Twenge and others, loneliness also has been on the rise among young people. So have self-focus, individualism, and narcissism.

Do you relate to any of this? Do you personally know a young person who seems to be struggling with their mental health? Do you notice how many youths seem too narrowly self-focused?

What can we, as adults, do to help?

The short answer: we can help young people find more awe.

New Research on Awe in Kids

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about a research article, published recently in the journal Psychological Science. In two studies, researchers randomly assigned some 8-13 year olds to watch an animated movie clip eliciting awe, some to a clip eliciting joy, and some to a clip eliciting a neutral (control) response. Results showed that, compared to the joy and control conditions, the kids led to feel awe more likely participated in an effortful task and more likely demonstrated generosity toward refugees (a group not their own). Those led to feel awe also experienced more of a parasympathetic, calming bodily reaction associated with social engagement.

Awe is an emotional response to something vast that transcends our current frame of reference. The scientists who conducted the awe studies speculate about various activities that may nurture awe in young people. For instance, parents, teachers, or other adults might connect kids to stories that are highly unusual or even magical; music with unexpected harmonies or shifts in energy; amazing theatrical, artistic, or athletic performances; big buildings like cathedrals; and beautiful places in the natural world.

Much of this stands in contrast to the common view that great literature, music, theater, art, and time spent in nature don’t have much real-world impact and that they are expendable from school curricula.

Applying This Research to Help Young People

Of course, many factors likely threaten youth mental health. Although I personally would love to see a nationwide prohibition of social media until the age of 18 – or at least a change in school policies such that times could be intentionally carved out during the school day when cell phones are not accessible to students – these changes lie largely beyond my control. As a parent, I could restrict my kids’ technology use – and I wish I had done that when they were younger – but I feel that, ultimately, in this culture, adding family restrictions may cause other problems. Overuse of technology seems to be more of a systemic, cultural problem.

A more effective, more practical strategy may be to help the young people in my life find more awe. I can do my best to encourage a love of reading, theater, music, art, and sports. I can enroll my kids in schools that are environmentally-focused. When I’m teaching, I can bring my classes outside, when possible. I can bring my son to a live concert. I can bring my nephew to the zoo.

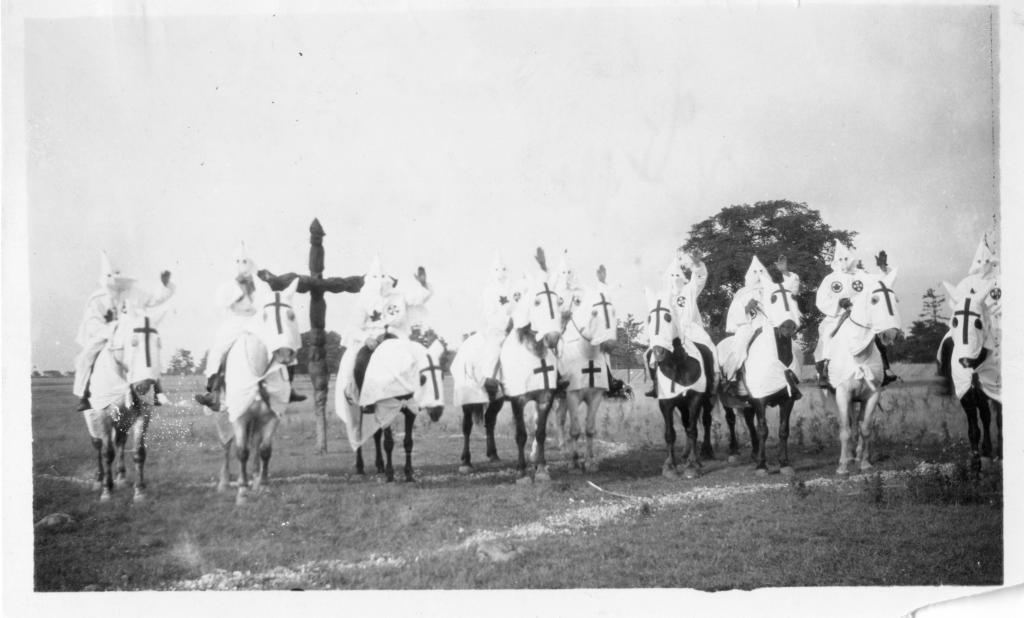

Why Religious Fundamentalism Can Inspire Hatred (and what to do about it)

Intermixed with much of the worst of human history is a religious motivation. This can be seen in the involvement of a religious motivation in the genocide committed against American Indians and the Holocaust. More recently, this can be seen in the motivation behind tragedies such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the January 6 attack on the United States Capital. Other examples include the involvement of religion in motivating prejudice and violence directed toward members of the LGBTQ population and various cases of religious persecution.

As Blaise Pascal once reflected: “human beings never do evil so completely and so joyously as when they do it from a religious motivation.”

How can great world religions – which generally teach love, compassion, and justice – become powerful instruments of prejudice and violence?

Although acts of religiously-inspired hatred are complex and caused by many variables, one common factor concerns religious fundamentalism.

Religious fundamentalism involves a rigid kind of certainty in the possession of the “one truth” and the “one way” to live. It typically relies on a literal interpretation of a sacred text and an absolute reliance on that text. Other sources of knowing what’s true or other ways of determining what’s valuable are rejected – such as when science or a different group offers an alternative perspective – in favor of what’s unquestioningly accepted within the group.

With this all comes a strong urge for fundamentalists to form a sense of who are “insiders” and who are “outsiders.” Explicitly or implicitly, it’s easy for all of us to believe members of our groups are superior, while others are inferior. One way for religious fundamentalists to address this is to develop an evangelical zeal to bring outsiders to the inside through attempts to convert them. However, when individuals reject their arguments or invitations, fundamentalists can develop even stronger attitudes against them, to the point where outsiders can become seen as less than their human equals, sometimes even leading to consciously or unconsciously dehumanizing them. At this point, prejudice and violence toward members of the outgroup become more likely.

Because fundamentalist groups also tend to draw like-minded people to their communities, individuals in these groups often decrease or completely lose contact with those different from themselves. As a result, the kinds of reality checks most people tend to naturally have happen to them when they interact with people different from them become less likely, creating the conditions for stronger stereotypes and prejudices to develop.

Continue readingOther Options for Mental Health Care

The United States is experiencing a mental health crisis. The prevalence of mental illness and emotional symptoms of distress generally have been on the rise for many years, but the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a surge. Emotional problems are particularly increasing among adolescents and young adults, especially among females and especially among individuals who identify under the LGBTQ umbrella.

For example, in the recently published Healthy Minds Study of over 350,000 college students representing 373 American colleges and universities, over 60% met criteria for one or more mental health problem. Since 2013, symptoms of depression have increased 135%, anxiety 110%, eating disorders 96%, and thoughts of suicide 64%. Overall flourishing also decreased in this timeframe by 33%.

Mental illness isn’t just about personal suffering, although it clearly includes this. Mental illness also impacts many kinds of relationships, the ability to work effectively, and the success of students. For instance, depression doubles the risk of a college student dropping out without graduating. To the extent that individuals are unable to fulfill their roles in these areas, our country and world will suffer as well.

Part of this mental health crisis stems from the lack of access to evidence-based help. Waiting lists have lengthened, hospital beds are short, and the ability to see a mental health professional regularly has been diminished. Expert help is hard to come by and practitioners are burned out. Organizations that could supply mental health support – such as business, colleges, and religious organizations – do not have the staffing or training to do so.

The lack of access to good mental health care also demonstrates a societal inequity. In the Healthy Minds Study mentioned above, students of color were the least likely to use mental health services. Although Arab American students had experienced a 22% increase in the prevalence of mental health problems, they were 18% less likely to access treatment, compared with 2013. This gap in mental health access across the races parallels the gap in achievement often demonstrated in work and school across the races, and may play a causal role.

Although the availability of evidence-based psychotherapy and medicine needs to be improved, especially for individuals with serious illness, other options also may be increasingly needed. The Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies provides a list of recommended self-help books based on evidence-based cognitive-behavioral principles at their website. Digital psychoeducation programs based on cognitive-behavioral principles (such as Learn to Live) are increasingly offered through partnerships with health plans, businesses, and colleges. Phone apps based on mindfulness techniques (such as the Healthy Minds Innovations app) are offered for free to anyone. In general, research on these options suggest they reduce symptoms as much as traditional psychotherapy and medication, perhaps especially for those who are mildly or moderately distressed.

Continue readingThe Science and Practice of a Good Life

Two years ago today, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic. Now, after two years of living with various restrictions, many of us are entering a new phase, with some long-neglected life options returning. We may be asking ourselves: “how do I want to live now?” As we wrestle with this question – aided by the greater perspective and wisdom that comes from adversity – we may benefit from considering what constitutes, for us, a good life.

Psychological scientists increasingly focus on three different visions of a good life.

First, a life of happiness tends to be characterized by pleasure, stability, and comfort. (On the flip side, a life of happiness seeks to minimize pain, instability, and discomfort.) Of course, we all find happiness in different ways, but research often shows how the experience of close relationships plays a vital role in this vision of a good life. For example, in a recent study, research participants rated having a party to be the daily activity most likely to make them happy. I’m also reminded of Elizabeth Gilbert’s quest for a good life in her bestselling book “Eat, Pray, Love,” and how her pursuit of pleasure translated for her to eating really good food in Italy. If we want to focus our lives on happiness, we might do well to habitually ask ourselves, “what would I most enjoy?”

A second vision for a good life involves the pursuit of meaning, characterized by purpose, coherence, and significance. (On the other hand, a life of meaning seeks to avoid aimlessness, fragmentation, and insignificance.) People living this kind of good life often feel like they are making the world somehow better. Religious and spiritual activities often play an important role. For instance, in “Eat, Pray, Love,” Elizabeth Gilbert sought a life of devotion through yoga and meditation in India. We can concentrate on this vision of a good life by consistently asking ourselves, “what would be most meaningful?”

Increasingly, psychologists of the good life discuss a third vision: a psychologically rich life. This kind of life comes with a variety of interesting experiences that produce changes in perspective. (The opposite of a psychologically rich life may be found in a lifestyle characterized by repetition, boredom, and stagnation.) Research shows how study abroad experiences in college, for example, tend to increase feelings of psychological richness. Live music, in-person art, and many other kinds of stimulating, mind-opening experiences may play a special role in nurturing a psychologically rich life as well. For those of us wanting to pursue this vision of a good life, we might do well to frequently ask ourselves, “what would be most interesting?”

The Top 5 Posts for 2021

It’s been another year for the books. Somehow, in the midst of everything, more and more people seem to be following this blog.

As a way to review the year, below are my most-read articles that I wrote during 2021. If you haven’t had a chance to read these articles yet, you may be interested in checking them out.

5. Awe Decreases Political Polarization

In a time of great political polarization, this post explores new research on how experiences of awe may help bring people together.

4. Awe as a Resource for Coping with Stress

Based on new research, this post examines how awe experiences diminish the stress response.

Honestly, this is one of my favorite things I’ve ever written. It explores how I try to experience the coziness of Winter.

2. The Science of Motivating Others

This blog post briefly went viral on Psychology Today. It relates to an old and new interest I have in the science of motivation.

1. Six Skills We Need as Citizens Who Can’t Agree on Scientific Facts

This was an opinion piece I published with the Star Tribune this Summer. It was born out of my frustration with people who can’t seem to accept facts.

Share this:

Contentment Whatever the Circumstances

No matter how people feel about Christianity, I imagine most would aspire to the place St. Paul arrived at when he declared:

“I have learned to be content whatever the circumstances.” (Philippians 4:11)

I don’t know about you, but I was hoping for a better 2021 than 2020. If anything, for me personally, 2021 brought more problems, not fewer. Family troubles intensified. Work conflict increased. And, though we have vaccines to mitigate the worst outcomes from COVID-19, the pandemic has not faded.

I wonder what Paul meant when he said he was content whatever the circumstances. Based on other things he wrote, I don’t believe he avoided or ignored the awful parts of life. After all, Paul was in prison at the time he wrote these words. In general, avoiding or ignoring difficult circumstances seems like a recipe for only increasing one’s problems in life long-term. So, the question I’m left with is: how can we honestly face life’s struggles and still be content?

Part of my prayer practice is to actively listen for God. Inspired by the Quakers, I set aside time regularly to be silent and see if any wisdom “bubbles up” or “reveals itself.” I also “listen for God” in other ways, such as in conversations I have with friends. Sometimes, if I can listen carefully enough (a big “if”), something does indeed “bubble up.” Sometimes, some of that “received wisdom” has stood the test of time.

I don’t know if any of this does a good job of answering my question – and I surely have a long way to go before I get to the place Paul was at – but when I consider how to honestly face life’s struggles and still be content, I find myself continually returning to four points of inspiration.

1. “Accept and expect irresolution.”

This is something my friend, the author and peace activist, John Noltner, likes to say. I clearly remember many years ago attending a small workshop with John when I first heard him emphasize this point. Years later, in silence, these words came back to me and they have stuck with me since.

I think part of what makes it so difficult to find contentment is we often look for final and complete resolution of our problems. Then, and only then, we believe, can we really reclaim our contentment.

Continue readingToday: The Day to Do Something

My friend, Dr. Robert Fisch, often reflects on his life by remembering an old Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times.” Dr. Fisch’s “curse” included living amid the “interesting times” of the Holocaust, Soviet oppression, and the clinical challenges of working as a pediatrician with children presenting with the devastating disease of phenylketonuria (PKU). However, part of Dr. Fisch’s story includes rising to these challenges of his time. He resisted the Holocaust and Soviet oppression, and he found a way to help treat PKU. In these ways, Dr. Fisch ultimately contributed to a more humane and just world.

The past two years have clearly been “interesting” and maybe feel “cursed” as well. COVID impacted every facet of our lives from early 2020 to Spring of 2021. Racial tensions became more evident with the murder of George Floyd and the racial reckoning that followed. Political polarization drove people apart and contributed to an insurrection on our democracy on January 6, 2021. And, now, within a matter of days, we’re learning we face a “different virus,” to quote Dr. Anthony Fauci, that has the potential to upend life again. Finally, we’ve faced a heat, drought, and regular bout of air quality alerts that awakens us, if we haven’t been awakened before, to the reality of climate change in my state of Minnesota.

These are historic challenges. I can imagine a day when my children or grandchildren may look back at these times we’re living in at this time as if they presented a set of forks in the road. “We the people” and we individuals each have choices to make about what futures we will create, the sides of history on which we will stand. As Dr. Fisch has said:

“Yesterday is past. Tomorrow is a wish. Today is the only time in which to do something.”